Who Learns Languages Faster: Adults or Kids?

Who Learns Languages Faster: Adults or Kids?

Lin is a 5-year-old Chinese girl, and she invites her 27-year old mom to learn English with her.

“Oh sweetie, mommy is too old to learn a new language!” Her mom, Wei, replies.

“That’s not true!” Their English teacher claims and they decide to do an experiment.

Lin and Wei have an instructional English class in China for one hour.

Guess who learns more?

27-year-old Wei learns more.

This advantage of faster learning persists even after 5 years, when they both keep learning English as a foreign language in China.

Surprised?

In a parallel universe, Lin and Wei directly immigrate to America. They don’t have time for classes so they are learning English in the non-instructional immersion-context of their daily lives. Guess who learns more in 1 year?

Wei, mom, learns faster in the first year, but Lin, daughter, catches up in 2 years and eventually surpasses her mom overall in 7 years; though it does not mean 12-year-old Lin can write a resume or publish a paper like her mom.

Surprised again?

In another alternate universe, Wei might start learning English in America at 22 and reach native-like proficiency. Such a universe exists, but is less common.

The fear of being too old to learn a new language

We cannot tell you how many times we have heard the complaint “I am just too old to learn a new language!” Perhaps you’ve even thought this yourself. What if we told you your age could actually be an advantage in language learning?

Though human’s general learning ability declines as people age, including language learning ability; the fear of simply being “too old” has its root in the “critical period hypothesis“, which assumes irreversible biological changes prevent you from being a successful language learner as you get older. In other words, it’s the “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks” mentality. This, however, is merely a hypothesis.

We do know that age can be associated with many factors. For instance, in the example above, Wei’s well-developed Chinese interferes with English learning, or Wei’s mind is too crowded with family and work to make room for pure language learning, or Wei’s strong identity as Chinese prevent her from speaking a second language, or Wei’s concern with grammar surpasses her will to try to speak.

Not only do we have good reason to be more optimistic about language learning as adults, this kind of pessimism can also hurt our ability to learn. After all, how can you learn a language if you perceive yourself to be incapable of doing so?

Lin vs. Wei: Who is a better language learner?

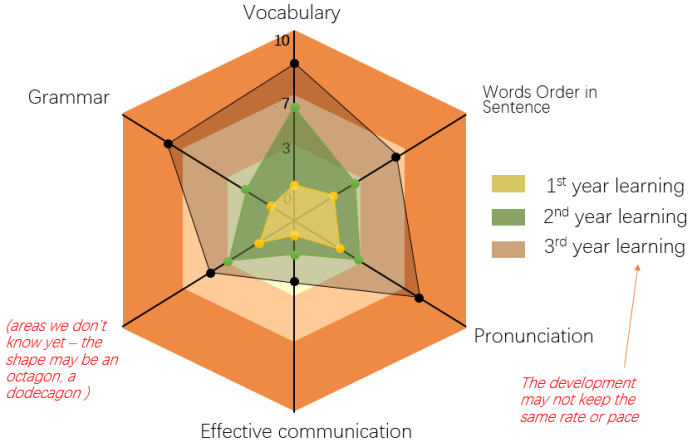

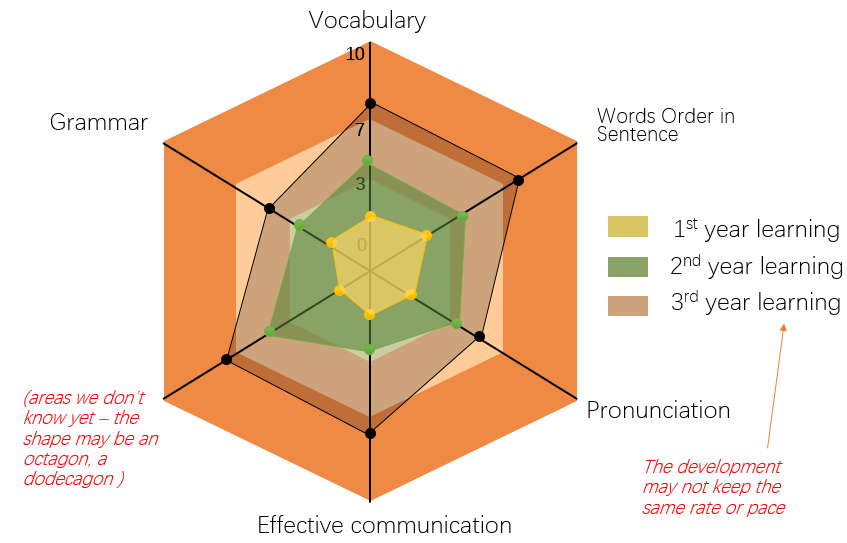

Instead of a one-dimensional bar diagram (figure 1), language learning is a multi-dimensional radar chart (figure 2).

figure 1.

Figure 2. Lin Language development Wei’s Language development

As we can see, Lin and Wei have different language learning advantages.

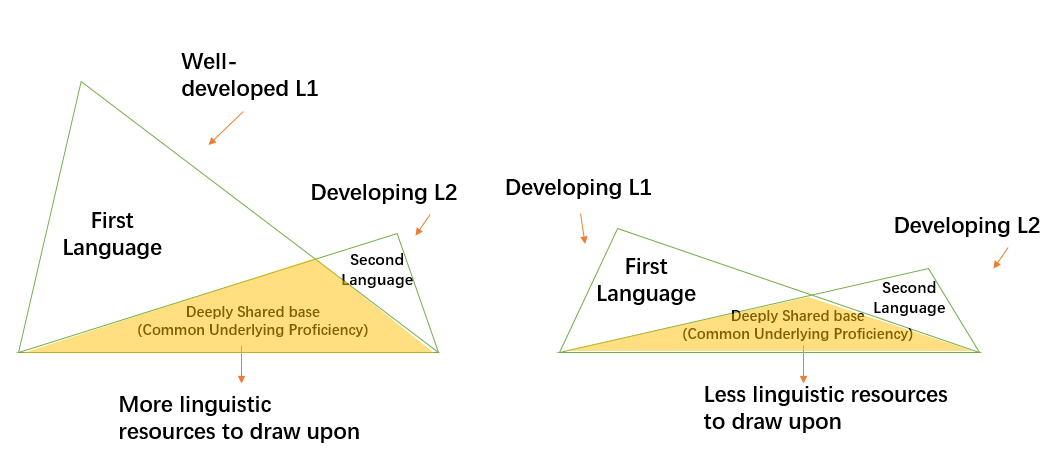

As an adult, Wei is better equipped with knowledge about language because of her well-developed first language, Chinese. She already knows basic language concepts such as “verb” “noun” and “sentence structure”, and can apply such knowledge into English learning, since languages do share a deep, common base. Lin, on the contrary, is still developing her first language and mapping out the panorama of language (figure 3).

Figure 3. Wei Lin

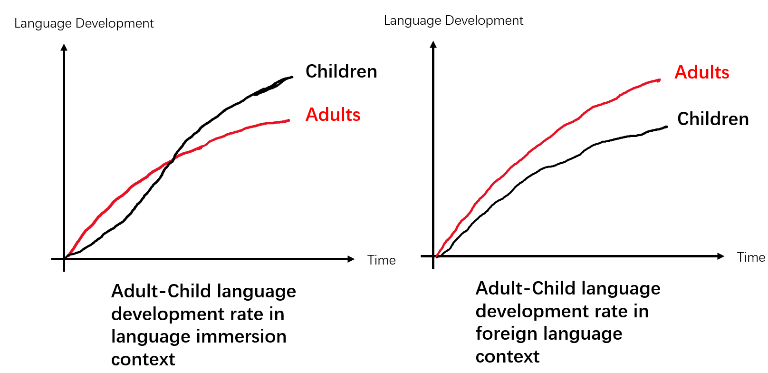

Wei also has a faster learning rate. She learns more content than Lin in a class (25 min) or in immersion, non-instructional environment (up to a year) because of cognitive maturation and previous language knowledge. In short, adults are better at problem solving which helps them decode languages. This initial advantage can be lost in 3-5 years in immersion context, though. In foreign language context (studying a language in a classroom setting in a country where it is not the majority language), however, the advantage persists (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Wei has stronger motivation because of clear goals. Lin may only be motivated by sweets and praises from teachers; Wei may seek a career opportunity or a new possibility for life. Ultimately, motivation to learn a language determines a lot in successful language acquisition.

Wei’s cognitive maturation is also a powerful aid for language learning, especially when the language learning tasks involves complex thinking. For example, in instructional context, Wei usually comprehends and applies grammar rules faster than Lin. Dealing with language tasks that involve cognitive capacity, adults usually excel children.

Lin’s ultimate attainment (overall language performance based on fully-developed language proficiency) can reach native speaker level, while it is harder for Wei, especially in terms of pronunciation. However, pronunciation really comes after communication, and many people assume too little tolerance and patience from native speakers. Studies also suggest that children are better at learning language implicitly, just like the way they learn to ride a bicycle. But how we learn a language does not equate with how well we learn it.

There are, however, some simple tactics for language acquisition children naturally use adults can try to help in their language learning process.

What Adult Students Can Learn From Children

- Communication before grammar

There is trade-off between accuracy and fluency – put communication first because that’s what language is for.

- Verbal Repetition of words & sentences as many times as possible.

It helps commit words to memory and practice pronunciation.

- Learn through topics that interest you

Why do you think toddlers have no problems remembering names of 20 different dinosaurs?

- Connect language learning to the actual world

If you want to remember “grapefruit” in Chinese, eat it when learning to say it; learning household items in German? Label everything in your house!

- Use your time wisely – small Link, high frequency

Give yourself plenty of time and learn over a long period in small amounts to ensure that the new information is retained long-term and is easy to access. Taking months and years to work on our language proficiency, with frequent revisions, repetitions, working on one thing for a longer while, and going back to old things has a positive effect on our long-term outcomes.

- Stick with it!

Don’t give up, don’t take breaks, don’t postpone or delay, keep going, just like kids do!

References

“Age effects in language learning: controversial, but crucial to understand,” by Robert Dekeyser

Why Any Adult Can Learn a Second Language Like Their Younger Self

Lourdes Ortega, Understanding Second Language Acquisition, chapter 2

Second language acquisition – essential information